|

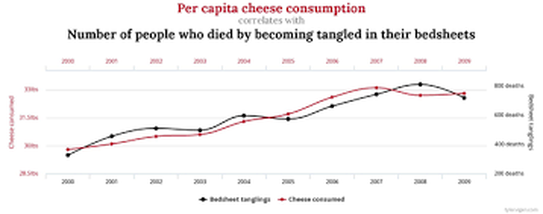

I've been asked to republish a thought-provoking article I wrote back in 2017 ago for Placenta Services Australia. The CDC dropped a case report allegedly linking placenta capsule consumption to late-onset Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in infants. The aftermath brought a whirlwind of discussions and speculation in the birth and encapsulation spheres. So, grab a cuppa and join me as we delve into the facts surrounding this case and the intriguing world of placenta encapsulation. Oh, and a quick heads-up: This piece is all about sharing info, not doling out medical advice. Let's get informed! Placenta Services Australia response On the 30th June 2017, the Centres for Disease Control and Infection (CDC) in America published a report associating the consumption of placenta capsules by a mother with the late onset of Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection of her infant . Since then there has been numerous news reports, articles, discussions within the birth and parenting worlds on social media and speculation by many. But what do we actually know about this case and about the process of placenta encapsulation? What is Group B Strep? Group B Streptococcus, otherwise known as Streptococcus agalactiae is a gram-positive circular bacteria that tends to grow in pairs or short chains. GBS is a commensal bacterium reported to be present in 15% - 40% of the population. It lives in the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tract of humans usually without any harm to us. It can however cause significant problems in newborns if they become infected. Infection in neonates occurs from exposure to their mother’s genital tract colonisation during labour or birth or from the amniotic fluid is the membranes are ruptured prematurely and the bacteria travels up into the uterus and is known as early-onset infection. If the baby contracts GBS after the first week, it is known as late-onset infection and is believed to be transmitted from the mother through her breastmilk in a rare number of cases, or from environmental and community sources such as hospitals and their staff . Antibiotic treatment of the mother to eradicate genital tract group B streptococci has shown to only be useful temporarily and reinfection may occur. What is Placenta Encapsulation? Placenta encapsulation is the process of drying, crushing and putting the desiccated placenta powder into capsules for the mother to consume postnatally. This is usually done through a business, the mother’s doula or midwife or in a few cases through family and friends. Anybody who encapsulates should follow industry standard protocols including the use of personal protective equipment, maintenance of the cold chain, heating at correct temperatures and sanitisation of all areas and equipment with the correct disinfectants. What did the CDC report and what questions does it raise? The mother’s screening test for GBS at 37 weeks was negative - Your GBS status can change between when the test was taken and when you go into labour. The culture test can also show false negatives and it is likely this was the case as early-onset infection comes from the mother. The infant was treated with antibiotics for the first infection - there are known cases of recurrent infection of GBS after treatment and the bacteria were shown to be identical in each case as was reported here by the CDC. This raises the possibility that the first antibiotic treatment was ineffective and allowed persistent colonisation of the newborn. The mother’s expressed breast milk was GBS negative and serial exams did not reveal a source of the recurrent infection being transmitted from the mother - so where did it come from? Was the mother retested? Was the placenta swabbed before being collected? This seems to be in conflict with the CDC statement “the final diagnosis was late-onset GBS disease attributable to high maternal colonization” Were hospital staff in contact with the baby tested ? The strain of GBS isolated by the CDC known as the ST-17 clone, is known to have a strong association in epidemiological studies due to its specific virulence factors . Surely this adds to the plausibility that it was a recurrent infection rather than reinfection from the mother? The CDC report states that “ transmission from other colonized household members could not be ruled out” The CDC report does not give the exact temperature at which the placenta was processed, instead it gives a range of temperatures from the processing company’s website based on the different processing methods. Even if processed by using what is commonly known as the raw method, the placenta should be heated to reach a core temperature of 75℃ before lowering to the ‘raw foods’ temp. Encapsulators should also ask about infections when collecting their client’s placenta. The client can then be counselled on appropriate processing methods if it is safe to proceed. If infections such as chorioamnionitis are present, then the placenta should not be encapsulated. If the client becomes aware of an infection in herself or her baby between the time her placenta is collected and the capsules are returned, she should notify the placenta services specialist so that proper information can be given, which may include disposal of the prepared capsules instead of consumption. The CDC states that “The placenta encapsulation process does not per se eradicate infectious pathogens” yet provides no reference for this statement. If we look at the (limited) research on placenta encapsulation, the preliminary results from Jena University Hospital has found that “The preparation of placental tissue has a clear effect on the microbial contamination: dehydration causes a drastic germ reduction, steaming followed by dehydration causes an even greater reduction of microbial species. Regarding to foodstuff regulations of the European Union, no “unsafe” organisms were detected in our samples.” So the CDC has reported one case of placenta consumption that coincided with the newborn sadly acquiring a disease, yet how many women have consumed their placenta with no ill effects? Data collected by Placenta Services Australia shows that over 90% of the nearly 400 women surveyed, reported that they experienced no ill effects from consuming their placenta and those that did were minor effects such as headaches, nausea or even unpleasant aftertaste . Let’s remember that correlation (if there even is correlation here) does not equal causation, however we should all be mindful to take the possible implications seriously. This report from the CDC seems to raise more questions than it does answers, using placenta encapsulation as the scapegoat. What can you do to ensure a safer encapsulation experience? 1. Become informed about the risks of Group B strep to you and your baby and how it can be detected and treated. Here are some links for further reading: Group B Strep in Pregnancy: Evidence for Antibiotics and Alternatives. April 9, 2013 by Rebecca Dekker https://evidencebasedbirth.com/groupbstrep/ More about GBS and How to Help Protect Your Baby https://www.groupbstrepinternational.org/more-about-gbs-and-how-to-help-protect-your-baby.html Group B Strep Resources by Sara Wickham http://www.sarawickham.com/topic-resources/group-b-strep-resources/ 2. Question your placenta services provider about their processes for transporting and storing your placenta, making your capsules and sanitising their prep area and equipment. 3. Enforce hand washing for everyone before touching your baby or your placenta capsules. See the World Health Organisation for How to Wash Your Hands Properly 4. Steaming your placenta to a core temperature of 55℃ for 30 minutes will inactive Streptococcus agalactiae. The temperatures reached by a dehydrator alone (usually a top of 70℃) is insufficient to inactivate it. Dry heat of 160-170 ºC for at least 1 hour is required. The bacteria is also susceptible to 1% sodium hypochlorite (bleach) which should be used by all placenta services providers to sanitise their equipment and prep area. References

Buser GL, Mató S, Zhang AY, Metcalf BJ, Beall B, Thomas AR. Notes from the Field: Late-Onset Infant Group B Streptococcus Infection Associated with Maternal Consumption of Capsules Containing Dehydrated Placenta — Oregon, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:677–678. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6625a4 Barcaite E, Bartusevicius A, Tameliene R, Kliucinskas M, Maleckiene L, Nadisauskiene R (2008). "Prevalence of maternal group B streptococcal colonisation in European countries". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 87: 260–271. Burianová I, Paulová M, Cermák P, Janota J. Group B streptococcus colonization of breast milk of group B streptococcus positive mothers. J Hum Lact. 2013 Nov;29(4):586-90. doi: 10.1177/0890334413479448. Epub 2013 Mar 22. Edwards MS, Nizet V (2011). Group B streptococcal infections. Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant (7th. ed.). Elsevier. pp. 419–469. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3. Streptococcus agalactiae, Pathogen Safety Data Sheet, Public Health Agency of Canada. 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/streptococcus-agalactiae-eng.php Edina H. Moylett, Marisol Fernandez, Marcia A. Rench, Melissa E. Hickman, Carol J. Baker; A 5-Year Review of Recurrent Group B Streptococcal Disease: Lessons from Twin Infants. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30 (2): 282-287. doi: 10.1086/313655 Six A, Joubrel C, Tazi A, Poyart C. Maternal and perinatal infections to Streptococcus agalactiae. Presse Med. 2014 Jun;43(6 Pt 1):706-14. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2014.04.008. Epub 2014 May 20. Based on the recommended temperature to eliminate Salmonella, Campylobacter and a 6D heat process for Listeria monocytogenes. Food Standards Australia New Zealand Safe Food Australia, A Guide To The Food Safety Standards, Third Edition. November 2016. https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/publications/Documents/Safe%20Food%20Australia/Appendix%203%20-%20Limits%20for%20food%20processes.pdf Sophia Johnson, Jana Pastuschek, and Prof. Dr. Med. Udo Markert. A scientific approach to placenta remedies: What hormones are found in placenta tissue? April 2017. https://experiment.com/u/DKKnUQ Results from PSA Data Collection. http://www.placentaservices.com.au/psa-data-collection-results.html Streptococcus agalactiae, Pathogen Safety Data Sheet, Public Health Agency of Canada. 2011. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/lab-bio/res/psds-ftss/streptococcus-agalactiae-eng.php

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

freebiesPrepare for an easier fourth trimester with these 25 Secrets From A Postnatal Doula!

blogs

All

About MeKelly Harper is the owner of Elemental Beginnings Doula & Placenta Services in Adelaide. She provides sleep consultancy, placenta encapsulation and doula services to families during pregnancy, birth and in their fourth trimester. |

|

© 2023 Elemental Beginnings |

|

PREGNANCY, BIRTH & POSTNATAL SUPPORT DELIVERED WITH ❤ THROUGHOUT ADELAIDE & SURROUNDS